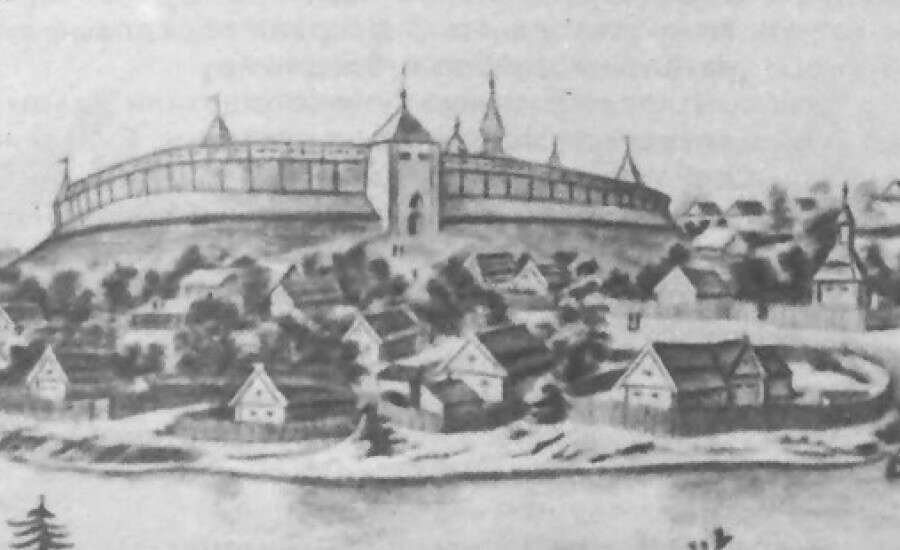

Moscow in the 12-13th centuries

The foundation of the city

The capital city appeared where the Moscow River meets the Negilinnay River. Archeologists say settlements on the territory of Moscow appeared thousands years ago. According to legends, the great duke Yuri Vladimirivich Dolgoruky invited duke Svyatoslav Igorevich (from "Slovo o polku Igoreve") to the site of current-day Moscow and they had a feast, after which the city was founded.

Moscow opened trade routes to Oka and Volga to everyone from Russia's northern and southern territories, from Ryazan and Smolensk, and between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries Moscow became a dominant city - the symbol of Russian people.

The first Duke of Moscow was Vladimir Vsevolodovich(1194-1228), who inherited Moscow from his father Vsevolod III. He didn't do anything of note.

Moscow in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries

The forefather of the dynasty of Moscow Dukes was a son of Alexander Nevsky - Daniil Alexandrovich. He started to gather piece of land around Moscow. And very soon became the territorial center of Russia. In 1326 the residence of Russian metropolitans (orthodox bishops) was moved from Tver to Moscow - an event of a great importance.

There were numerous attacks on Moscow. In 1382 the tatar khan Tohtamysh occupied Moscow. 24 thousand citizens were killed, and the Kremlin was burned to the ground. In 1382 Moscow was destroyed by a fire. Since that time chronicles started mentioning a "Kreml" (Kremlin) which was made out of wood and stone and looked like that until 1485.

The Rise of Moscow

Daniil Aleksandrovich, the youngest son of Nevsky, founded the principality of Muscovy based in the city of Moscow, which eventually expelled the Tartars from Russia. Well-situated in the central river system of Russia and surrounded by protective forests and marshes, Muscovy was at first only a vassal of Vladimir, but soon it absorbed its parent state. A major factor in the ascendancy of Muscovy was the cooperation of its rulers with the Mongol overlords, who granted them the title of Grand Prince of Russia and made them agents for collecting the Tartar tribute from the Russian principalities. The principality's prestige was further enhanced when it became the center of the Russian Orthodox Church. Its head, the metropolitan, fled from Kiev to Vladimir in 1299 and a few years later established the permanent headquarters of the Church in Moscow.

By the middle of the 14th century, the power of the Mongols was declining, and the Grand Princes felt able to openly oppose the Mongol yoke. In 1380, at Kulikovo on the Don River, the khan was defeated, and although this hard-fought victory did not end Tartar rule of Russia, it did bring great fame to the Grand Prince. Moscow's leadership in Russia was now firmly based and by the middle of the fourteenth century its territory had greatly expanded through purchase, war, and marriage.

Kremlin in the times of Ivan III

Kremlin in the times of Ivan III

Ivan III, the Great

In the 14th century, the grand princes of Muscovy began gathering Russian lands to increase the population and wealth under their rule. The most successful practitioner of this process was Ivan III, the Great (1462-1505), who laid the foundations for a Russian national state. A contemporary of the Tudors and other "new monarchs" in Western Europe, Ivan more than doubled his territories by placing most of north Russia under the rule of Moscow, and he proclaimed his absolute sovereignty over all Russian princes and nobles. Refusing further tribute to the Tartars, Ivan initiated a series of attacks that opened the way for the complete defeat of the declining Golden Horde, now divided into several khanates.

Ivan III was the first Muscovite ruler to use the title of "Tsar", derived from "Caesar", and he viewed Moscow as the Third Rome, the successor of Constantinople, the "New Rome". (Since Rome fell in 410 and the Byzantine Empire in 1453 to the Ottoman Turks, Moscow concluded that it now fell to the "Third Rome" to save Christian civilization.) Ivan competed with his powerful northwestern rival Lithuania for control over some of the semi-independent former principalities of Kievan Rus' in the upper Dnieper and Donets River basins. Through the defections of some princes, border skirmishes, and a long, inconclusive war with Lithuania that ended only in 1503, Ivan III was able to push westward, and Muscovy tripled in size under his rule.

Internal consolidation accompanied this outward expansion of the state. By the 15th century, the rulers of Moscow considered the entire Russian territory their collective property. Various semi-independent princes still claimed specific territories, but Ivan III forced the lesser princes to acknowledge the grand prince of Muscovy and his descendants as unquestioned rulers, with control over military, judicial, and foreign affairs. Gradually, the Muscovite ruler emerged as a powerful, autocratic ruler - a tsar.

Ivan IV, the Terrible

The development of the tsar's autocratic powers reached a peak during the reign of Ivan IV (1547-1584), and he became known as "Ivan the Terrible." Ivan strengthened the position of the tsar to an unprecedented degree: he ruthlessly subordinated the nobles to his will, exiling or executing many on the slightest provocation. Nevertheless, Ivan was a farsighted statesman who promulgated a new code of laws, reformed the morals of the clergy, and built the great St. Basil's Cathedral that still stands in Moscow's Red Square.

Time of Troubles

Ivan's death in 1584 was followed by a period of civil wars known as the "Time of Troubles". These troubles related to the succession and resurgence of the power of the nobility.

The autocracy survived the "Time of Troubles" and the rule of weak or corrupt tsars because of the strength of the government's central bureaucracy. Government functionaries continued to serve, regardless of the ruler's legitimacy or the faction controlling the throne. The succession disputes during the "Time of Troubles" caused the loss of much territory to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Sweden during the wars such as the Dymitriads, the Ingrian War and the Smolensk War. Recovery for Russia came in the mid-17th century, when successful wars with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1654-1667) brought substantial territorial gains, including Smolensk, Kiev and the eastern half of Ukraine.

Kremlin in the 17th century

The Romanovs

Order was restored in 1613 when Michael Romanov, the grandnephew of Ivan the Terrible, was elected to the throne by a national assembly that included representatives from fifty cities. The Romanov dynasty ruled Russia until 1917.

The immediate task of the new dynasty was to restore order. Fortunately for Moscow, its major enemies, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Sweden, were engaged in a bitter conflict with each other, which provided Muscovy the opportunity to make peace with Sweden in 1617 and to sign a truce with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1619.

Rather than risk their estates in more civil war, the great nobles or boyars cooperated with the first Romanovs, enabling them to finish the work of bureaucratic centralization. The state required service from both the old and the new nobility, primarily in the military. In return the tsars allowed the boyars to complete the process of enserfing the peasants.

In the preceding century, the state had gradually curtailed peasants' rights to move from one landlord to another. With the state now fully sanctioning serfdom, runaway peasants became state fugitives. Landlords had complete power over their peasants and bought, sold, traded, and mortgaged them. Together the state and the nobles placed the overwhelming burden of taxation on the peasants, whose rate was 100 times greater in the mid-17th century than it had been a century earlier. In addition, middle-class urban tradesmen and craftsmen were taxed, and, like the serfs, were forbidden to change residence. All segments of the population were subject to military levy and to special taxes.

Peasant uprisings

The greatest peasant uprising in 17th century Europe erupted in 1667, in a period when peasant disorders were endemic. As the Cossacks reacted against the growing centralization of the state, serfs joined their revolts and escaped from their landlords by joining them. The Cossack rebel Stenka Razin led his followers up the Volga River, inciting peasant uprisings and replacing local governments with Cossack rule. The tsar's army finally crushed his forces in 1670; a year later Stenka was captured and beheaded. The uprising and the resulting repression that ended the last of the mid-century crises entailed the deaths of a significant share of the peasant population in the affected areas.

Moscow in the 19th century

Moscow from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries

The period at the beginning of the seventeenth is known in history as Smutnoe Vremya (Time of Troubles). During this period the rulers changed frequently, and Moscow was occupied by Poland. During few years of poor harvests a severe famine took away thousands of lives. In 1612 Minin and Duke Pogarsky liberated Moscow from Polish occupation. The monument to Minin and Posharsky, which appeared on Red square in 1818, commemorates this even with the inscription "To Minin and Duke Pogarsky from grateful Russia". In 1613 Mikhail Fedorovich Romanov became tsar.

In the middle of the eighteenth century Moscow gradually transformed itself into a national cultural center. In 1755 Moscow University, along with two gymnasiums (schools), was founded. Here Moscow's independent newspaper, Moskovskie Vedomosty (Moscow News) was published. Its first magazine Poleznoe Uveselenie (Useful Joy), edited by Mikhail Heraskov, was printed here as well.

In 1812 Napoleon sent his troops to Moscow. It was a difficult, prolonged war, during which Moscow was again razed to the ground. As a memorial to those who died in the war (in which Russian eventually triumphed) the Cathedral of God's Ascension was built. All citizens of Moscow took part in the erection of the cathedral, and it was finally completed in 1880. The Triumfalnie Vorota (triumphal gates), located on Tverskaya Ulitsa, were also built as a memory of the war. The idea to build Triumfalnie Vorota belonged to emperor Nikolay I, and they were finally opened for the public view only in 1834, on the twentieth anniversary of the end of the Patriotic War.

The cultural life of Moscow of that period was colorful and interesting. Many well-known magazines were published at that time. In 1802 Nikolay Karamzin founded the Vestnik Evropi (The Messenger of Europe) magazine. Another magazine, "Russky Vestnik" (Russian Messenger), mainly covered Russian history, especially the history of Moscow.

In 1812 the "Association of Russian Literature Lovers" was founded. Many prominent writers such as Pushkin, Turgenev, Ostrovsky, Tolstoy were the members of this society, which, by the way, functioned for almost 100 years.

Moscow in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the banishment of French army from Moscow became the main reason for the cultural and political renaissance of the city.

There was also a healthy dose of political dissent in Moscow. Many Decembrists (participants in an uprising in St. Petersburg in 1825) were born here; in fact 50 of them studied at Moscow University. The first Decembrist organization, called "the Military Society" was founded in the city. Another significant event was the arrival of Alexander Pushkin to the city, where in the residences of Sobolevsky and Venevitinov he read his tragedy "Boris Godunov", based on the great Russian historian Karamzin's account of the aforementioned Time of Troubles.

Domestic industry grew fast, many new factories appeared, industrial equipment was renovated, the railroad network became broader and trade flourished. In the 1860s the number of Moscow citizens was 400 000; in 1897 it grew to 1 million. The opening of Pushkin Monument, which attracted many famous people from different parts of Russia, forever cemented the poet's iconic status. The celebration lasted for four days and included a particularly impressive speech by Dostoevsky.

In between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when Russia was on the brink of revolution, the situation in Moscow was very tense. At the beginning of the twentieth century many people became victims of revolution. Then there was civil war, economic struggle, and many political disruptions. All that was a heavy burden for Moscow. Then Germany attacked, and Moscow was seen as the only savior of Russia: while the city was still free, hope was still alive. The Germans came very close to Moscow and Stalin started to doubt whether they'd be able to prevent an attack on what was now the country's capital, however in Tula, on the border of the last outpost, the German troops were finally shattered. Moscow became a symbol of the courage and independence of the country during the great Patriotic War of 1941-1945. A memorial to those who died during the war on Poklonnaya Gora was built shortly after.